a

21st-century sound

What is a 21st-century sound? For our purposes, It’s music that sounds like it was created in this century and could not have been created in the 20th century, and that has a substantial market share. To explore the notion of a distinctive 21st-century sound, we sample music that is both innovative and commercially and critically successful.

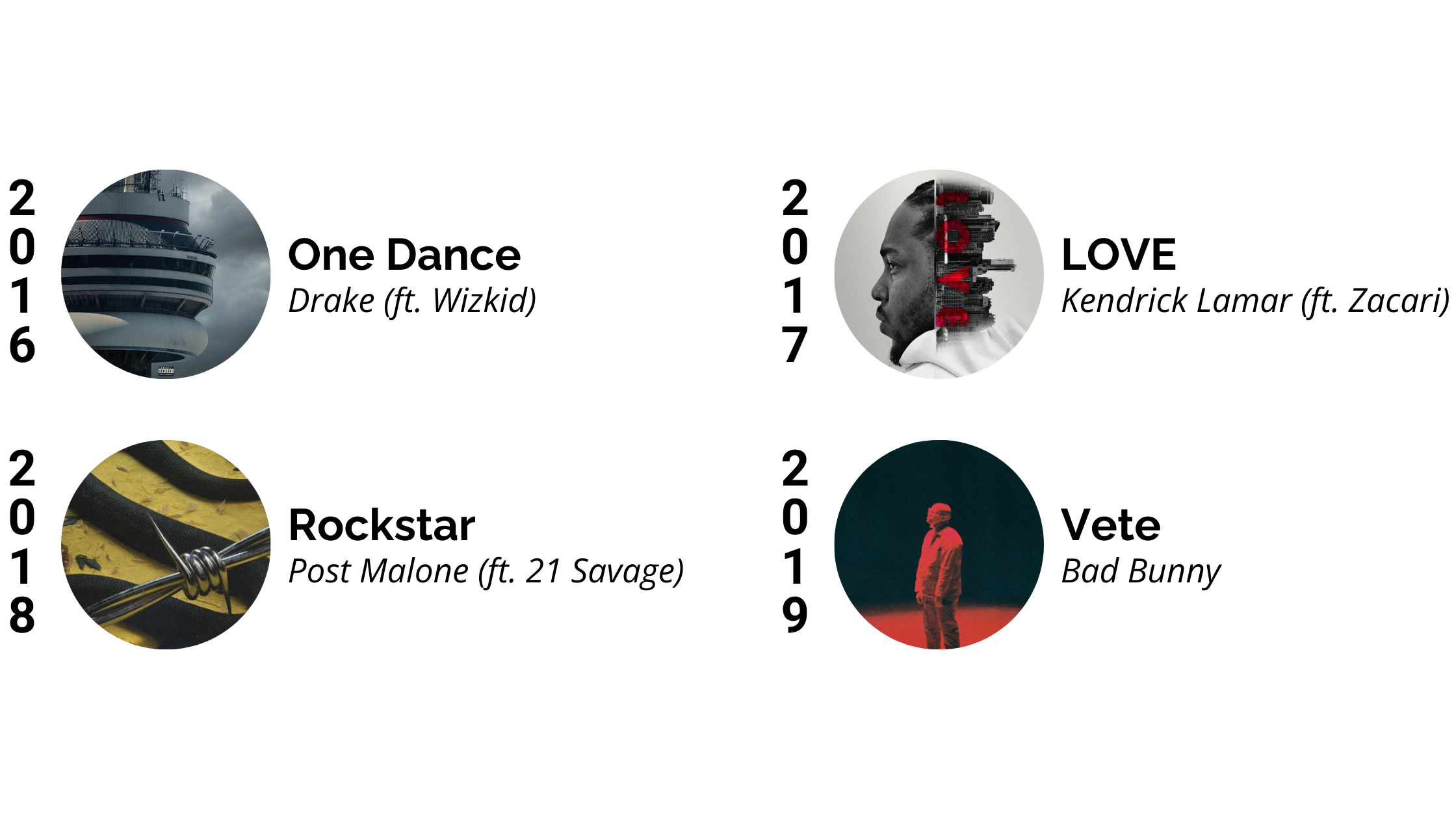

Here are four such tracks recorded between 2016 and 2019 that collectively exemplify musical features that have shaped a particularly influential 21st-century sound.

If you’re not already familiar with these tracks, you can hear them here:

The four tracks share four musical features:

1

Chord loops

2

Rhythmic signatures

3

Distinctive sound worlds

4

“Rappified” melodies

Chord Loops

In this music, a chord loop is a series of chords that is repeated without change in either chord choice or chord rhythm through most or even all of the track.

We almost always hear chords in a loop from the bottom up. The bass is typically the focal note of the chord, and it usually marks off the rhythm of chord change.

Here is an excerpt from Kendrick Lamar’s LOVE, featuring just bass and keys. In this excerpt, we can hear how the chords are literally built up from the bass note, by arpeggiating the chord tones. This excerpt illustrates the conditioning we’ve acquired listening to harmony from the bass up and through our familiarity with basic chord progressions. We hear the first chord as an F major chord even though it actually spells an inverted d minor triad. The faint extra notes reinforce that impression.

Chord progressions that repeat

The use of chord loops is not a 21st century innovation. The practice of creating music over a recurring bass line—and the chords that it implies—goes back centuries. Here are two still-familiar examples of this practice. The first comes from the late 17th century, the second is a 1960 doo-wop remake of the 1934 pop song “Blue Moon.” The Pachelbel bass line contains eight notes. It is a more elaborate form of the four-note pattern in “Blue Moon,” which comes in two interchangeable versions.

We hear excerpts from both works preceded by an amateur performance of the “Heart and Soul” progression. This is the progression most of us know experientially, because we’ve heard it in so much music.

What’s different about the four chord loops is their disassociation from a sense of key. In the examples above, we are clearly in a key, and the chord progression is essentially the same in all three.

That’s not the case in any of the four chord loops. None convey a sense of departure and return to a home chord by a well-established path. The two innovations in the four chord loops are relative ambiguity regarding key and the individuality of the chord choices.

In “One Dance,” both chords are incomplete chords —two different pitches— instead of the usual three-plus pitches. They are built on the first and fourth notes of a scale. The move of the bass in the first chord fills out the harmony, creating a minor tonic chord.

“LOVE” rotates between chords built on the first and fourth notes of a major scale

“Rockstar” has a more remote chord relationship: between chords built on the first and sixth notes of a minor scale.

“Vete” has a three-chord loop. All chords are incomplete, in that they contain only two notes. The two notes of the second chord are exceptional in this context because they do not map onto conventional major or minor triads. The third chord lasts twice as along as the other two. The harmony does not change even though the bass moves.

These details evidence that the approach to chord loops in these four tracks represents a clear departure from the functional chord progressions heard in the Pachelbel Canon, “Blue Moon,” and countless other musical works that use some or all of the “Heart and Soul” progression.

Consonant Atonality

We describe this effect of this approach as “consonant atonality.” “Consonant” means that the chords are comprised of tones that—literally—sound “good” together. There are centuries of precedent for what chords are consonant. “Atonality” emphasizes that fact that, despite sounding good together, the chords do not establish the key via a conventional route.

The distinctive chord loops in the four tracks are one dimension of the customization of existing practices. It’s one of the innovations that gives this music a 21st century sound. Rhythmic signatures are another.

Rhythmic Signatures

What we’ll call a “rhythmic signature” is a rhythmic pattern customized for a particular track, or extended section of a track. The raw material of a rhythmic signature is usually a generic rhythmic template or other familiar pattern. In this sampling, two of the four tracks build on a common rhythmic pattern heard for decades in calypso and soca, and more recently in Afrobeat. The rhythmic signature of “LOVE” is a customized rendering of the 16-beat rhythm widely heard since the 1980s. By contrast, the rhythmic signature of “Rockstar” is built on a distinctive rhythm that has no clear connection to a generic rhythmic template.

The creators of these four tracks relied mainly on three strategies for customizing the rhythm:

Creating a distinctive rhythmic pattern, typically a customized version of a more generic rhythmic template, and repeating it through most or all of the track

“Coloring” the (digital) drum track with a variety of percussive sounds

Adding rhythmic interest from pitched instruments like bass and keyboards.

The slides highlight these features as they are heard in the excerpts.

Distinctive Sound Worlds:

The continuing improvements in digital sound technology have created an enormously expanded sound palette—like going from 256 colors in early computers to 16.7 million in this century. Tech-savvy creators have used these capabilities to expand not only the range of sonorities but also the range of sound blends. As we will hear, there can be extraordinary subtlety in the mixing of sonorities. These more subtle variations can add variety to the unvarying chord loops and rhythmic signatures.

What stands out about the sound worlds of the four tracks is the difference from any one track to the other three. In this video, we hear each chord loop once. Despite some common features, e.g. the prominent bass and busy percussion parts, the contrasts come into sharp relief.

21st century instrumental backing

The three elements—harmony, rhythm, and sound—work in lockstep to provide consistent support throughout a track. Chord loops are the closest to a constant through the song. Typically, any change in the chords comes from enriching the harmony with additional pitches, rather than swapping out one chord for another. Rhythm tends to be more intermittent, but the rhythmic signatures are typically heard through most, if not all, of a track. Adding and subtracting sound layers is the most frequent variable. All of this usually happens modularly. The musical flow is articulated into modules of 16 beats, and change — such as the addition of a layer—more often occurs from one module to the next, rather than within, a module.

This instrumental backing provides a bed for vocal lines that are also remarkably consistent.

“Rappified” Melody

Most of the vocal lines on the four tracks share these four qualities:

They move at a fast pace; the words tumble out.

The melodic lines generally stay within a narrow range, and often features long strings of repeated notes.

Melodies feature considerable repetition, sometimes literal repetition, other times with slight variation.

The words flow in a steady, fast-moving stream, with relatively few pauses.

Here are excerpts from the tracks demonstrating these features.

The first three qualities are also heard in music before the 21st century. Chuck Berry’s verse/chorus blues songs, like “Maybellene” and “Johnny B. Goode,” are familiar examples. What most distinguishes the melodic approach in the excerpts below from earlier instances is the almost unbroken flow. There are gradations in the flow, but even more chorus-like sections like “I need a One Dance…..” and “I’m a....Rock star” are more active than choruses in much of the pre-rap music in the latter half of the 20th century. Sung raps replace the repeated riffs of 20th century pop, R&B, and rock.

This approach to melody is arguably the most conspicuous innovation in 21st century, if only because the words are the main focus of a song and because the practice has spread beyond hip-hop.

Reinventing Melody

For more than a decade, from the 1979 release of “Rapper’s Delight” through the early 1990s, rappers rapped without producing definite pitch. There was inflection in rappers’ delivery, but sounds were not sustained long enough to vibrate at a specific frequency. Instruments and samples playing definite pitches would be heard in the backing track, but not in the rap. And there were acts such as Public Enemy and Eric B. and Rakim whose music occasionally included few or no pitched sounds. The most prominent sounds were percussion sounds.

The emergence of rap was the final segment of a century-long pendulum swing from nothing-but-melody at the beginning of the 20th century to no-melody-at-all. However, in the early 1990s, the pendulum slowly started back toward melody. The first step in integrating rap and melody was to put them side by side—interpolating rap segments into a track, or vice versa. A second way of bringing rap and melody together was layering them: rap and melody heard simultaneously. The final step was sung rap. As we’ve heard, it was a new approach: melody decisively influenced by rap. This approach surfaced in a few hip-hop tracks during the 2000s, mainstreamed in the 2010s and continues to be a popular option.

Hip-hop has become melodically richer in the course of the 21st century, mainly through the use of these three strategies, singly and in combination. However, of these, only the sung rap belongs exclusively to the new century, for two reasons. One is that it came into use only after 2000. The other is that rap has influenced melodic writing in the 21st century, not only in hip-hop but also in pop, country, Latin, and other genres.

A 21st-century sound

The music we’ve been hearing has a distinctively 21st-century sound. Its innovation is not attributable to any single feature. Chord loops, rhythmic signatures, and distinctive sound worlds are customized continuations of late 20th century practices. Sung rap is new to the 21st century, although it was all but inevitable. Rather, it’s the cumulative impact of all four features interacting in a mutually reinforcing way. One innovative — and fascinating — aspect of this musical synergy is a different approach to musical time.

Dissolving the timeframe

The standard formula for organizing time in popular music since the ascent of rock and Motown in the 1960s is the verse / pre-chorus or bridge / chorus sequence. The flow is directed toward the chorus: we often hear the title phrase sung to a memorable riff. This is the arrival point within the section. As such, it articulates a relatively long span of time. As the song unfolds, we know where we are in the form by the clear differentiation between verse and chorus.

In the four tracks, the sense of periodic arrival is much more muted, because the contrast in the melody between verse(like) and chorus(like) sections is much less pronounced than in a typical pop/R&B/country song, and because harmony and rhythm retain the same patterns through most or even all of a track. The relentless regularity of the loop becomes the more prominent slower-moving rhythm. The effect is like hearing a clock tick but not seeing the face of the clock to learn how much time has passed. The abrupt end of each of the tracks does not convey any sense of resolution. There’s no anticipation that the track is coming to an end; it just stops.

This approach seems to resonate with the messages in the lyrics. In all four, there is no resolution. The lyrics seem to offer snapshots, rather than a story with a clear path from beginning to end. The situations described in the lyrics are complex and multilayered. A more conventional musical setting would have undercut the emotions communicated in the lyrics. The innovative approach used in all four tracks seems better suited to express musically the sense of the words.

These four tracks exemplify a significant innovative direction in popular music. It belongs to this century; it wasn’t part of the sound world of the late 20th century. It was significant not only for its novelty, but also because a lot of listeners heard it. All four recordings placed well on the charts.

These tracks represent a particularly intensive realization of three key developments in the century: the enormous expansion of sound possibilities, the customization of rhythm and harmony, and the “melodification” of rap. In the next part, we explore how these developments filtered into more traditional genres, through Lil Nas X and Billy Ray Cyrus’s “Old Town Road” Morgan Wallen’s “Last Night,” and two COVID-era songs by Taylor Swift.